- World of DaaS

- Posts

- Founder/Host of Dwarkesh Podcast Dwarkesh Patel

Founder/Host of Dwarkesh Podcast Dwarkesh Patel

AI Timelines, Productivity & Global Stagnation

Dwarkesh Patel is the creator and host of the Dwarkesh Podcast, where he interviews leading scientists, founders, and economists about AI, science, and progress. He’s known for his deep curiosity and ability to draw out original insights from top thinkers.

In this episode of World of DaaS, Dwarkesh and Auren discuss:

Why current AI models fall short of real economic impact

What’s missing in elite AI discourse

How to think clearly in a world full of noise

The hidden power of collective AI learning

1. AI's Limits Today: Promise vs. Practice

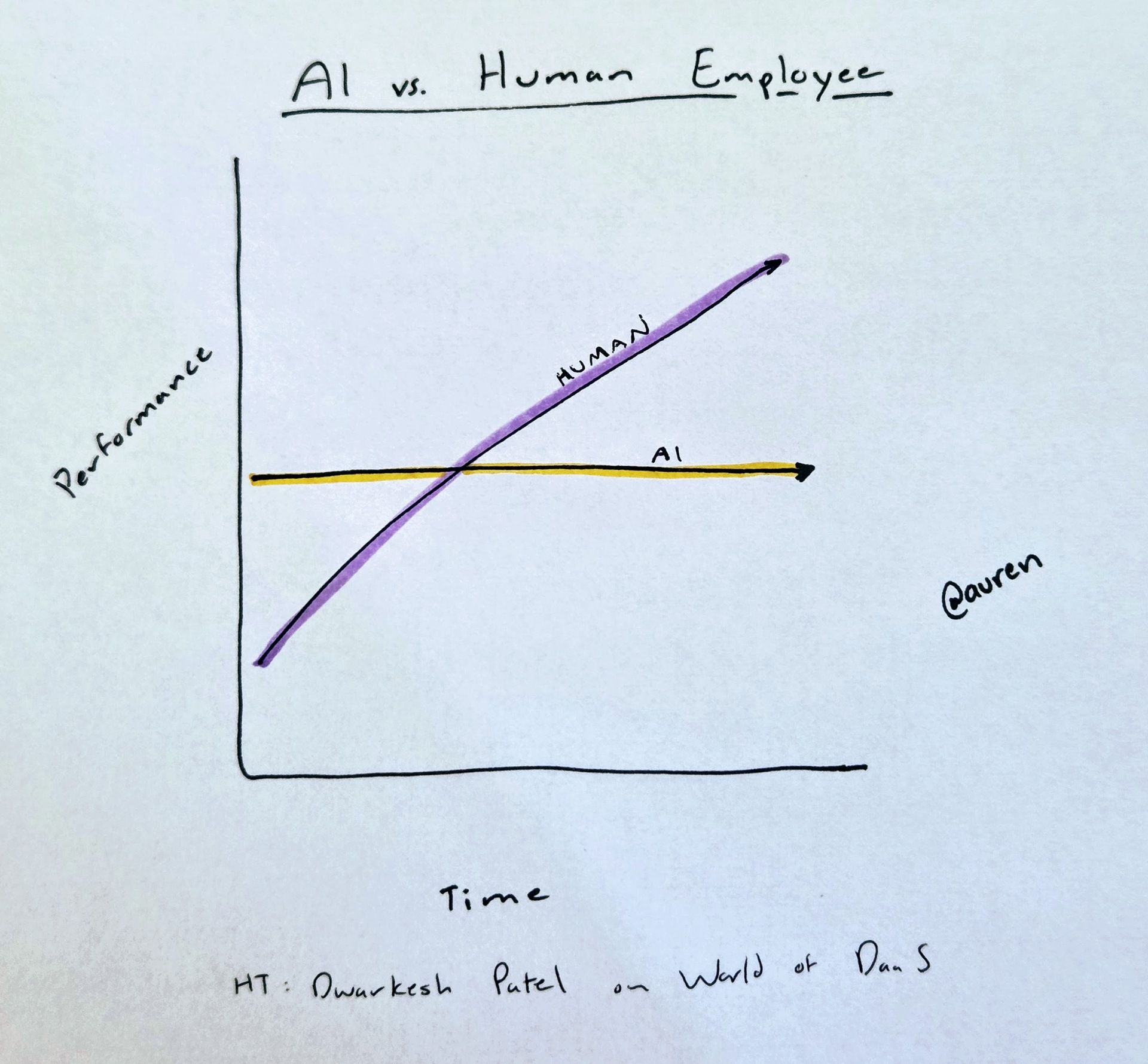

Dwarkesh Patel explains that while AI models are impressive, they haven’t delivered the economic impact many expect. He points to the lack of on-the-job learning as a key reason. Unlike humans, AI can’t build context or improve with repetition. Models perform reasonably well out of the box but reset after each task, which limits their usefulness in real work settings.

2. What We're Missing in the AI Conversation

Patel argues that too much attention is placed on benchmarks like coding or PhD exams, which don’t reflect the kind of work most people do. Real productivity comes from sustained execution over time, something current models can’t handle. He sees promise in future models that can use computers directly and in the potential of collective learning across many deployed copies of an AI.

3. Economic Divergence and the Mystery of Productivity

The two shift to global economics, using Japan and Europe as examples of once-strong regions now stuck in stagnation. Patel highlights the long-term damage of financial crises and how demographics and missed technology waves may also play a role. They also discuss how many white-collar workers may add negative value, yet remain employed because their impact is hard to measure.

4. Curiosity as a Discipline: Retention, Reflection, and Learning

Patel talks about cultivating curiosity by noticing confusion and using tools like spaced repetition and Socratic tutoring with LLMs. He believes retaining what you learn takes active effort, not just passive consumption. Both he and Auren reflect on how most people read or listen without remembering much, and that deep learning requires more structure and intention.

“Only part of the value humans bring is raw intellect. The rest is our ability to build context, learn from failures, and pick up small efficiencies over time.”

“Curiosity often comes from meditating on your own confusion. Once you realize what you don’t understand, you can’t stop thinking about it.”

“We underestimate the advantages AIs have not because they’re smart, but because they’re digital. Coordination, memory-sharing, and scale will matter more than IQ points.”

The full transcript of the podcast can be found below:

Auren Hoffman (00:00.886) Hello, fellow data nerds my guest today is Dwarkesh Patel. Dwarkesh is the host of the Dwarkesh podcast where he interviews leading scientists, founders, economists about AI science and progress before launching his podcast full-time. started computer science at UT Austin. Dwarkesh, welcome to World of DaaS. I'm very excited. I'm a huge listener of your podcast, of your writings. I'm a massive, massive fan. This is like a fan boy coming out here.

Dwarkesh Patel (00:17.006) Thank you for having me.

Dwarkesh Patel (00:27.714) Hahaha.

Auren Hoffman (00:29.094) And one of the things you just like, you've really interviewed just like tons and tons of super, super smart people. What do you think like people are most wrong about?

Dwarkesh Patel (00:37.166) Mmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (00:41.816) Hmm, depends by subject because there's guess on a wider range of topics, but on AI, I'd say that some of my guests have timelines that are too short. They expect the capabilities of AI to be much more valuable much sooner than I expect. This is not all my guess, that's the, if I did identify the thing I'm most likely to disagree with, some of my most recent guests, that would be it.

Auren Hoffman (01:10.85) And you, cause you're, not only a interviewer about AI, but you're a user of it, right? You're using these tools. And it's funny. Like every time I'm using them, I don't know if you're running the same thing. Like I run into some sort of limitation. Um, now that, that, that, that, and like, where I think it can do X, but it can only, it can't actually do that yet. Now that X keeps moving. So every few months, but for some reason I'm, constantly thinking it can do X now.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:15.735) Mm-hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:32.174) Mmm.

Auren Hoffman (01:40.234) when it can't. I don't know if you're running into similar or something similar.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:43.502) 100%. Very similar issues. And that's honestly made me update my views around the actual value of AI models today. I think sometimes people have this attitude, and I'm sure you run into this all the time, they think that the reason, you you can look at the revenue of OpenAI and it's on the order of 10 billion ARR. And that's like impressive, obviously, but it's less than Kohl's or McDonald's, right? So certainly not AGI.

And then the justification people have for this is, look, the management at Fortune 500 is too stodgy. They're not adopting these AI workflows, but what you really have is a baby AGI. And it just because people are too lazy to integrate these systems into work environments that they're not being utilized to their maximum potential. I think this is a very minor part of the reason that AI is not as widely deployed as you might naively expect based on how bullish people are about the AI models of today. I think the more important reason

is that it's genuinely hard to get human-like labor out of these models. And I've experienced this myself by trying to build these little LLM workflows for my podcast. I'm sure you have these kinds of things set up as well, right? Like getting into rewrite transcripts and find clips and so forth. And I've just been thinking about, why is it the case that I still have to hire a human for these tasks? Why can't I delegate these language in, language out tasks to language models? And fundamentally, I think the problem is

the lack of on the job training. These AI models do have an impressive list of capabilities right out of the box. They'll do any sort of language tasks you have like this. They'll do a five out of 10 job at it, which is higher than what a default human might do. the problem is they don't get better over time. At the end of a session, their whole memory gets purged. unlike an employee, like a human employee, they might not even be useful until like six months in.

But you're training them, they're building up all this context, they're learning from their failures, they're picking up these small efficiencies and improvements as they practice the task. So this lack of on the job training, I think is a huge bottleneck to unlocking the full value of these models. And I don't see an easy way to add that in right now.

Auren Hoffman (03:54.72) And, and, but it, the puck is moving though. Like the, is, it is moving, but it feels like my expectations are moving just as fast as the puck or I don't know if you're, and what I think should happen or, I don't know if I'm the, the, just a weird guy or that's like what everyone's feeling when they try to use these tools.

Dwarkesh Patel (03:59.598) Mmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (04:05.56) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (04:16.331) Hmm. I think it's fair to point out that our expectations keep shifting and this is a famous Famously, you the goal the goal push we always keep shipping on AI where every year can do a thing that we said it couldn't do before but now it's we say Well, we're still not there because of this X remaining thing now That's a fair objection that you or that's a fair rebuttal to say it look you're shifting the goalposts but another thing to notice is look if you do

If you keep hitting these benchmarks, if you do keep hitting, we pass a Turing test, right? Nobody noticed. We have models which ace math exams that are made for the smartest grad students in these challenging environments. And if we keep passing through these benchmarks, while at the same time not unlocking the economic value that is implied by AGI,

which at the minimum should be able to do white collar work, right? Which is worth tens of trillions of dollars every year in terms of wages paid to white collar workers. If we're not unlocking that while at the same time moving through these benchmarks, then it does make sense to shift the goalpost in the sense of asking, well, what is the remaining bottleneck that we didn't previously identify, which explains their lack of usefulness.

Auren Hoffman (05:32.908) What's your thought like what, where we're, what's going on or what's happening here?

Dwarkesh Patel (05:37.486) Yeah, I think a big part of it is this continual learning, this lack of on-the-job training, which I think is how humans mainly contribute value. Only part of the value humans bring in work is their raw intellect. The rest is this ability to build up context and interrogate their failures and pick up small efficiencies and improvements as they learn on the job. The other big thing is, of course, these models are just chatbots right now. And it's just very hard to...

be useful as a simple, like you ask it a question and it gives out an answer. That's not how most work happens. so sooner or later, we're going to see models which can actually interact with the computer in the full range of ways that a normal white collar worker can interact with the computer, including emails, browser, whatever other applications.

And of course, it can't do all white collar work until it can at least has a modality to access computer use. Now there's all these interesting questions about then how do you train models that are capable of using the computer in this way? Because you're not just doing pre-training on text the way these models are trained right now. But I think that will be a huge unlock as well.

Auren Hoffman (06:53.236) If you just think, mean, you, you have so much insight into just the elite conversation that's happening amongst people. What do you think is like overrepresented and what do you think is underrepresented in this elite conversation?

Dwarkesh Patel (07:06.646) Mmm.

I think people are just really stuck on reasoning or coding or...

Exams which test knowledge So there's famously this exam this benchmark released last year called humanities last exam and it was supposed to Well what it sounds like it was supposed to be this final benchmark And why was it supposed to be the final benchmark well because it asked the hardest PhD questions And of course if we can answer PhD questions, then you must be a GI right because that's the other smartest humans can do but that ignores that most work is just not constituted of

answering tough chemistry questions or answering math problems. Most work is just mundane, day in, day out. The things we take for granted because it comes so easily to us, just like executing on a project over the course of a month and backtracking when you notice you're going on a dead end, but which is not available to these models at all because of the fact that their context cannot accommodate a month-long task because of the fact that

They won't learn in the way that humans learn on the job because of the fact that they can't use computers

Auren Hoffman (08:25.696) It's interesting. Cause like, if I think of like my math, like the, the, you know, math all throughout college, I think the last math class that was useful to me in my daily life today was probably 10th grade. I, know, I think after that, I don't, I don't think I've really used that kind of math, even though it's probably important. Like, and maybe it's intellectually interesting. Like it wasn't useful in my own life.

Dwarkesh Patel (08:39.598) Hahaha.

Dwarkesh Patel (08:48.75) Yeah. Well, my day job is a podcaster, so the level of math I'm using is even smaller than that.

Auren Hoffman (08:56.96) Yeah, exactly. Like maybe you want to get some probability and statistics and a few other types of things that are out there. And when you think of like, okay, so you, one of the things that you're, you're really good at is, is identifying original thinking and, and, then bring that out on your podcasts. What w if you had to think through like the commonalities of these original thinkers, what is that? Like, what are, are there any?

Dwarkesh Patel (09:02.53) Right. Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (09:27.426) Hmm. Yeah, I think one thing that I really appreciate and has led to some of my best interviews, the people I have learned the most from is deep empirical grounding. I think it just really matters.

Auren Hoffman (09:43.852) What does that mean? What does empirical mean there?

Dwarkesh Patel (09:46.542) I think sometimes people just have this very like pie in the sky. Here's my grand ideas for how society works or something. You know, like here's the philosopher from the 18th century I read and how it explains everything. And more and more, I'm just like, I don't think that that kind of stuff is that valuable. I think it's more about like, read the main economics papers and like look at the big trends or in the case of AI, at just like measure the trends out in terms of how much

instead of having some grand take about what is the nature of intelligence, I think that has its place as well, but also noticing what are the trends in terms of how much compute is scaling every year versus how much can be explained of algorithmic progress and what is the uplift that software developers say they're experiencing. Even in terms of grand historical narratives, rather than having some take about some Rousseauian take or some Hobbesian take about is mankind screwed or

what is a primordial nature of man, just like looking at the population size over time and what has been the growth rates, like going back to 10,000 BC and trying to learn from that pattern rather than some abstract first principles thought.

Auren Hoffman (11:03.554) Okay. So it's really just like looking at the numbers and then maybe updating your beliefs based on how those are changing and stuff or.

Dwarkesh Patel (11:11.662) Yeah, think otherwise it's so easy to just, especially the kind of line of work I do, where there's no ultimate check, right? You can say whatever, and your theory might be correct, your theory might be wrong. And so it's really easy to get yourself in these loops of grand narratives. And I found it very useful when somebody just checks that with, here's the empirical evidence in other fields.

Now, one common failure mode when you get too much in the empirics is just closing yourself off to evidence in adjacent fields, which I think is also a bad idea. Like, you're just like, give me the numbers on AI, otherwise I don't want to hear that argument in the context of AI discussions. But there's also a way to be grounded when discussing other adjacent fields. So one of my favorite, Carl Schulman made this point to me. He's an AI forecaster, and he made this interesting argument about

look, how do we explain why scaling up AI models makes them smarter? And he noticed that there's been this research in primatology by this researcher, Susanna Herculina-Hussel, which shows that as you increase the brain size or the brain weight of primates between different primate species from lemurs or something to humans, their neuron count increases linearly, whereas with other kinds of species,

like rodents, that doesn't happen. Okay. Well, that is like a very interesting empirical result, which like tells us something about maybe what happened with humans is that we finally landed on a scalable brain architecture that, and then we were in a evolutionary niche, which like rewarded increases in intelligence. Anyways, that is like a sort of like totally different field that you're learning about AI from, but you're still not, you still have some, some like real thing that you're talking about rather than,

Here's what this 19th century philosopher had to say about the will and intelligence.

Auren Hoffman (13:15.65) Okay, if you think of like these...

you know, these kind of like big thinkers that are out there, there's this one kind of critique that it's hard to be a big thinker these days because you have to like specialize in a very, very narrow PhD. But then you kind of like meet all these like random people out there, like whether it's like Peter Thiel, Mark Andreessen, Tyler Cowan, like, they, seem to be really big thinkers. They seem to be thinking like across.

50 different fields and I would put yourself in one of the, as one of those people as well, who you just have like real diverse interests, real knowledge across many, many, many things. So are we, are we losing the big thinker? Are we losing the person who can think across things in today's world or are we not?

Dwarkesh Patel (14:02.764) Yeah, I I think all the people you mentioned are super smart and I'm fans of all of them. But I think those are great examples because I think those people are especially good in domains where they're, which they have like genuine understanding of and that understanding often comes with like genuine, real tangible

real tangible.

I don't want us to just say numbers because numbers is not what I'm referring to. For example, I Tyler is like, mean, Tyler is like, is he a big thinker? I mean, obviously he's a big thinker, but it's because he's a small thinker in a million different things. In any given subject, he will be able to go toe to toe in terms of, if you think this is why Japan's economy cratered, well, how do you explain this other pattern? How do you explain this result from this other paper? In some sense, is, whereas, I don't know, I feel like...

some of these other people in that list will just have this like, I read this book that was written in the 40s and this explains how the modern world works. And I think that's just basically useless. And I don't think it really does. And if you like really get into the nitty gritty, just like this, just a bunch of words, right? I don't know if I addressed the crux of your question, but.

Auren Hoffman (15:28.61) What are the things, mean, you kind of like, thought when I first kind of into you, I kind of got into you because you were like talking about AI, but you really do have these diverse interests. And one of the things I love the most about some of your podcasts were like, have this like whole series with Sarah Payne on Japan and you brought like Ken Robb on Tucker Japan. Like why, why is Japan so interesting to you?

Dwarkesh Patel (15:50.606) Hmm I don't know if it's a central interest of mine, but the reason I find the Rogoff interview so interesting Or his claims about Japan so interesting so Japan famously had the in the early 90s it had a famous crash It was actually after World War two Obviously Japan got decimated. I think in 1950s or 60s Japan's per capita GDP was like 20 % of America's

And then by 1989, Japan's GDP per capita, at least in pure nominal terms, is 125 % of America's, which is to say that it went from being this destroyed nation to richer than America on a per capita basis. And then it crashes again, and it hasn't recovered for the last three decades. The GDP per capita in Japan is now less than 50 % of America's.

Which is just like shocking and then the question is why did that happen? Ken Rogoff who is a former chief economist at the IMF and he was on my podcast and he said this was actually the result of Interventions the Japanese government made at the behest of US pressure Specifically appreciating their currency and deregulating their financial markets faster than they should have and This just caused a huge financial crisis

And his claim is that unwinding financial crises is just a super tricky problem because it's not like a sort of like near term shock where you can, know, like we had the 2008 recession, eventually recover, supply recovers. But in this case, you just have so much bad debt that needs to be unraveled.

Anyways, a big update from me from that example is just that how bad financial crisis can be. That not only are they a short term...

Dwarkesh Patel (17:53.438) short-term pain but could they can permanently alter the growth trajectory of a country now many people have responded to that claim by Rogoff by saying look he's underestimating the impact of demographics that Japan is just a much older society and if you also compare Japan to other countries in East Asia like South Korea South Korea is obviously wealthier than North Korea or China on a per capita basis but it's also not doing as well as America and so this could have to do with the nature of you know

high-end electronics was just not the most competitive industry in the 21st century as it was in the late 20th century. So maybe it's more to do with demographics and what industry, like what things are exporting. But maybe a bigger issue that, or a bigger question I've been thinking about, and Japan is just one example of this, is how much of the world is simply not doing that well right now? We're in America and America has been doing great for many, many decades. And we're just quite used to the stock market. Like stock market goes up.

There's some amount of stability, new businesses are created, there's growth, there's new technology. And as much as we complain, that's been the pattern. Whereas you just look at different parts of Europe, you look at parts of East Asia, you look at even China now. It's just remarkable how much of the world really does seem stuck.

Auren Hoffman (19:11.618) It is interesting because like 2008 Europe is like the GDP of Europe is like roughly the same as the U S and maybe has more people. So per capita, it's like slightly lower. And then in that, in that kind of timeframe since then, the 17 years since then, we just, why divergence between the two and is, is it because maybe they didn't handle the crisis better? Or I don't even understand why that

that divergences happens at such a rate.

Dwarkesh Patel (19:42.302) Mm-hmm. I haven't heard either. It's I feel it's quite mysterious They also missed out on the internet wave, which I think has been a huge part of why Between the internet and between energy abundance with fracking I think has been a big like source of tailwind I mean that's quite interesting in itself that if not for two or three key inputs like this America would also be in a pretty bad position like imagine if fracking was not a thing America would be in a pretty bad position or imagine if big tech didn't end up being a thing

our pensions would be in trouble. You subtract that from the S &P returns, and it's a very different picture.

Auren Hoffman (20:19.586) And that just may come with like, okay, if you overregulate too much, you might just miss a wave that you don't know about, like the fracking wave, which could have hit Europe but didn't because of, you a whole bunch of different reasons there.

Dwarkesh Patel (20:26.19) Totally.

Dwarkesh Patel (20:32.108) Yeah, totally. I would be very curious to hear from economists about what they think the main causes of Europe's slowdown are. mean, one that I hear often is the labor market inflexibility, the fact that it's so hard to hire and fire people really limits the dynamism of those economies. I don't know if you have a theory on what's up with Europe.

Auren Hoffman (20:49.792) I don't know enough, but my guess is that's not totally it because it's easier to hire and fire, I believe, in Eastern Europe than Western Europe. And so you would just think there'd be more arbitrage. It could be like in the US where it's harder to have unions in the South than the North, so more jobs move to the South. But it just doesn't seem like it's happening at that rate there.

Dwarkesh Patel (21:01.134) Mmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (21:11.244) Yeah. And what's also crazy, think in Italy, this might be wrong, so somebody will let me know, I think productivity per hour has not increased since the 90s or some ridiculous amount of time, which is crazy to think about given the fact that we've had all this technology in the meantime. have internet, advances in logistics and energy and whatever. And the fact that the net impact of that is still

Zero presumably because other things are reducing productivity. This is also a pattern in China So since 2008 if you just look at aggregate the way you calculate productivity is you just take out You look at output you look at how much the inputs increased capital and labor and then whatever is not accounted by that Must be the productivity number and since 2008 I think China's Total factor productivity has also been flat Yeah, yeah, and this one explanation for this is that

Auren Hoffman (22:04.619) really? I didn't know that.

What's the theory behind it?

Dwarkesh Patel (22:11.17) My explanation is that they did a huge stimulus after 2008. So their reaction to the financial crisis was, this clearly shows that just market-driven growth will lead us to some sort of financial crisis. We need to manage this investment. And so they did a huge investment boom, which has resulted in these ghost towns, as they're called, or the huge leverage that the local government's building out these huge

infrastructure projects that then are now becoming less and less marginally useful. Because it wasn't directed by the market, a lot of this investment, some of it was, it just wasn't as productive. And so the aggregate productivity numbers are actually like surprisingly flat.

Auren Hoffman (22:59.65) I wasn't in the workforce 40 years ago, but I, I do believe that at least today there are a lot of people, a significant minority of people, at least in the U S that are negative productivity. and I don't know if that has gone up over time, but I believe it has. I believe there is this weird, like in some ways, like companies have this bargain with.

Dwarkesh Patel (23:14.094) Hahaha

Auren Hoffman (23:27.606) the government and with society where they have these extra folks there and they keep them there. and so there's just, there's actually a lot of people who not, who are not just zero, but they're actually making the company worse. and, and so, and it's just like hard to see it in the numbers that there's all these people who are way more productive and there's people who are dragging them down.

Dwarkesh Patel (23:41.73) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (23:50.936) But what is the sort of market explanation for why wouldn't companies just fire, or like why wouldn't the companies that decide to fire just out-compete the ones who don't?

Auren Hoffman (23:58.848) I don't know. but I don't, I don't totally understand it, but if you just like, even if you are like the most capitalist, you know, which is like the private equity firms and stuff, you think they're the most capitalist out there. They just want to win. And then you actually, if you actually interact with firms that are like run by private equity firms, like they're not run better. Usually my opinion.

And it's unclear why, like they're still bloated. They still have all this bureaucracy. They still do like all these random things that don't, that probably don't add value to probably add negative value. All these like weird committees internally and stuff and all these weird processes that don't probably help things and just kind of like make people move much, much slower. So I'm really not sure why, why it may be just ingrained in people's head.

If everyone's doing it, then it doesn't like really matter to out compete. If enough people start.

Dwarkesh Patel (24:52.706) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (24:58.912) Yeah, I've never worked a real job. So I have like no sort of first hand experience of what or first hand. My intuition is that

My intuition is that there might actually just be some surprising amount of value in these people. One, because I think markets work, I think it would, unless there's some other reason this distortion is created, I think it would be corrected for it. But maybe the other is this sort Chesterton's fence kind of thing, where even though we don't realize why the fence is there or what these extra people are doing, there might be some value that we're...

Now, mean, obviously there are sectors in which this is not the case, like NGOs or something, right? Or government. It would be very easy to understand why there's not a direct incentive to have efficient headcount. But how many extra workers does McDonald's have or Walmart have or a lot of these firms that employ a lot of people? I'd be surprised if it's like...

Auren Hoffman (25:56.514) So I would say more on the white collar than blue collar. I think blue collar, they're actually, there's a direct correlation to the output there where I was in the white collar. think it's, it's, it's very mysterious.

Dwarkesh Patel (25:59.522) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (26:08.451) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (26:12.526) So maybe the explanation for this distortion is that everybody knows that, 20 % of your employees are net negative value. But in white collar work, since there's no way to identify who those 20 % are, you'd be worse off by just indiscriminately firing or firing based on the signals you think you have. And so maybe it's a measurement problem. so it's rational for you to keep these people on board because the remaining 80 % are worthwhile that you can't just randomly get rid of people.

I wonder if that could explain the distortion.

Auren Hoffman (26:44.672) It makes it, you know, if you remember like four years ago when Metta started doing all these layoffs, they, did them very, they did a very small percentage at a time. did have many, layoffs, each one very small, like in, the single digit percentages. And everyone will tell you that's the wrong way to do it. Everyone says you should cut big and then announce to the team. We'll never doing a layoff again, because it's so bad for morale. And maybe the theory is like, well, they just did it. They couldn't.

Dwarkesh Patel (26:59.758) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (27:06.904) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (27:10.787) Yeah.

Auren Hoffman (27:13.9) cut that big because they had no idea who to cut. And so they had to do these scalpels very small over time to actually make it happen. And okay, we'll remove this layer of middle management, see what happens and then kind of adjust and then move this other layer and see what happens and adjust, et cetera.

Dwarkesh Patel (27:16.31) Interesting.

Dwarkesh Patel (27:30.252) Hmm. Yeah, interesting. More like lipo section instead of amputation. I think...

Auren Hoffman (27:36.714) Yeah, yeah, exactly. But if you light bow enough, then you have the same effect.

Dwarkesh Patel (27:42.176) Right. I think instead of Elon's companies that like Elon saying is, you should cut enough that you have to hire people back. Like this is the same thing of like if you've never missed a plane, then you were arriving to the airport too early. Yeah, but yeah, potentially just as some sort of like

Auren Hoffman (28:05.472) Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (28:12.366) pain threshold that you're not willing to go through.

Auren Hoffman (28:16.608) Yeah, exactly. One of my friends is investor has a similar theory about scams, which is like you need to have a relatively decently high scam rate where people scammed you out of your money. Otherwise you're never going to you're never you're not believing enough in the future.

Dwarkesh Patel (28:23.011) Mmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (28:29.664) Hmm

Dwarkesh Patel (28:34.476) Hmm, interesting. Yeah.

Auren Hoffman (28:35.956) And so the theory is like, if you, if it's like actually investing in Theranos or FTX, like that's not necessarily a bad thing, as long as you're not doing too big of a percentage of your investments in these things. If you spend all your time not doing that, then

Dwarkesh Patel (28:48.14) Right. Yeah. I think, I think FTX might've cost more money to investors, not in the raw investments they made in FTX, but in the, in the risk aversion that that created. And not, not just like normal risk aversion, but like specifically, I noticed this in AI where the big people who have a lot of money are making these bets in wrapper companies like cursor and perplexity and so forth.

Auren Hoffman (29:02.274) Correct.

Dwarkesh Patel (29:17.634) which I think might be fine bets, but are not to me as compelling as, because I believe that future AIs will be so much more powerful given these unlocks that are coming down the line with computer use and continual learning. think that's sort of like the things underlying that basic research or that the unlocking of those key capabilities rather than building wrappers on top of the existing abilities. I think that building that base layer is more valuable, but people are not willing to invest in it as much as it would make sense to me too because

Auren Hoffman (29:46.466) Sorry, but just to double click on that, just to like, wait, cause there's not that many companies that are building like the real underlying layer that's out there. So wouldn't that just like really confine the number of things you can invest in there in the AI world?

Dwarkesh Patel (29:46.584) They, after FTX, they're like, we need to see, yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (29:57.25) Right.

Dwarkesh Patel (30:05.742) It would in terms of just if you need to want to invest in a foundation lab, but I think there's gonna be Well, there's the physical compute itself, you know, you could invest in the components that go into building the chips Nvidia I think is probably like Nvidia is part like priceton, but you know, the the HBMs the SK Hynix is whatever. Yeah then

Auren Hoffman (30:16.277) Okay, yep.

Yep, or the energy or something.

Auren Hoffman (30:27.798) Yep. Brock.

Dwarkesh Patel (30:33.122) Then I think there's like the other components to trading, which are not raw compute, but which are other companies involved in the training. I don't know, like people who are building data sets or something, or have novel techniques there. I guess if I had more ideas, would, I would stop becoming a podcaster. But, but I certainly feel like right now just pouring money into, some people have the mentality like, look, we want to be grounded and therefore we want to see.

raw user numbers. And who has a lot of user numbers? Well, it's just wrapper companies, Because wrappers are who have users. And then they have inflated valuations, which might be merited in the sense that AI is going to be such a big deal that even they will be worth more. But I think it's relatively less undervalued as compared to the other parts of the stack, don't have a clear ARR, of, sorry, not ARR, but monthly active user type flashing life.

Auren Hoffman (31:29.762) The problem is with the, some of these research things that are out there, like their valuations aren't, may have zero ARR and their valuations are the same as another one that has a hundred million ARR and growing, you know, a hundred percent year over year. And so it's, it's hard to know where you should put your money.

Dwarkesh Patel (31:42.08) yeah.

100%.

Dwarkesh Patel (31:51.5) That's definitely true, yeah, agreed.

Auren Hoffman (31:54.05) So if one was like super cheap, would, yeah, it's great. Yeah. And maybe you should just be giving your money to, you know, Hinton's lab or something like that. And you donating it somewhere there.

Dwarkesh Patel (31:59.288) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (32:05.646) Right, yeah

Auren Hoffman (32:09.698) How do you, how do you, do you, are you an angel investor? How do you think about like that side of things? Like, cause you, have a very unique view of the world. Like you could, you in some ways, you could be a great investor. When I asked Tyler this, was like, no, I don't invest. don't, I have no desire to do it. I invest in people, like giving money away to people and seeing what they can do with it, but not to make a financial return for myself.

Dwarkesh Patel (32:27.459) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (32:32.866) Hmm. It's also crazy how much Tyler has accelerated so many different ecosystems, but even within AI, which is the one have visibility on and which is, don't think his primary focus at all. There's many people I know who are doing very interesting things who in some way can source themselves back to Tyler and the initial 20 K career grant that he gave them. So.

Auren Hoffman (33:00.086) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (33:00.398) Even if he's not receiving, I mean, guess if he was in position to receive the financial dividends from all the surplus value he's created, I think he'd be a multi-billionaire.

Auren Hoffman (33:09.43) Well, I honestly, I think like, I mean, for most people, even when they make billions of dollars, they, then they just spend it on other things like respectability or other, you know, status or other types of things. feel like Tyler has, he's gotten that billions of dollars of status and respectability back in some sort of way. Like everyone, the whole, the whole ecosystem really appreciates him in a way that, you know,

Dwarkesh Patel (33:27.982) Mmm.

Auren Hoffman (33:38.338) in a way that they maybe wouldn't appreciate him if he was just a billionaire.

Dwarkesh Patel (33:43.01) Yeah, this reminds me of this quote that Patrick McKinsey has about being a salaryman in Japan, where he says, look, you might be wondering why are Japanese salarymen willing to work so hard for so little money? And his answer is, in other parts of the world, you work hard, so you get paid a lot, and you spend that money to buy status. And Japanese conglomerates have figured out a way to cut out the middle man and just pay you in status.

But anyways, it's your original question about, I've got to figure out something to do with the podcast ad money. I once in a while, I'm not actively doing it, but I have friends who often start or are working on interesting things. And maybe like this year I've started seeing if I can be involved in some way, just if something falls in my lap, basically.

Auren Hoffman (34:41.772) What you've said, most people are kind of sleeping on like the collective AI advantages. Like how do we shift our mental map from the smart tools to the smarter, let's say ecosystems.

Dwarkesh Patel (34:55.831) Mmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (35:00.396) Yeah, I think people...

are underestimating, when you think about AI, you're just thinking about the intelligence of an individual copy of a model. And I think this leads people to ignore the unique advantages that AI have, which have nothing to with the raw intelligence, but the fact that they are digital. Obviously, humans, a lot of the value humans have also comes from the fact that we can cooperate with each other. We can form firms and institutions and governments and so forth. But this ability to cooperate and coordinate will be

so much stronger with AIs. mean, one obvious way is, OK, suppose this continual learning thing is solved, right? So suppose AI can actually learn on the job. And my take is that once this is possible,

Auren Hoffman (35:42.274) It can have memory and it's error.

Dwarkesh Patel (35:45.836) Yeah, and I'm not sure if memory really captures what this is. I think we really don't even have a good mental framework for what it is humans are doing that makes you so much more valuable in six months after you start the job than you are day one. But suppose we get that going in AIs. A human who learns on the job is upskilling in the specific job they're at.

Suppose an AI model is widely deployed through the economy and it's learning how to do different jobs across the economy. It can learn from the experience of all of its copies. So a single model is potentially learning how to get better at every single white collar job to begin with. And even if there's no more software progress after this point, That we're not making like, found some new way to train models. That alone is potentially enough for like what looks like a broadly deployed intelligence explosion.

This thing is not functionally becoming super intelligence. And that's one of the many ways you could have these sort of collective advantages because of the fact that they're digital that humans don't have. Yeah, I don't know how we make people more aware of it. I think it's probably hard for even us to sort of anticipate in advance just because predicting the future is very hard. What the implications of these collective advantages are, but you can even lower bound it to these kinds of really wild outcomes.

Auren Hoffman (37:11.212) Nope. So many of, you think of our listeners of this podcast, world of death, so many of them lead data companies or work at data companies. And we, we haven't yet seen like an explosion of revenues to these data companies from the AI boom. what, if you were kind of, what would you be thinking about if you were working or leading one of these data companies?

Dwarkesh Patel (37:25.87) Mm.

Dwarkesh Patel (37:35.871) What kind of data?

Auren Hoffman (37:37.57) I mean, people have so many different kinds of random things that they sell. Data about some widget. mean, usually data is about four nouns, right? Like either about people, places, products, or companies, right? And then they could be crossed for each other. They're sometimes crossed with time and price, right? So you could have like, data about molecules would be about a product or data about some person out there and what they're doing or whatever it might be.

Dwarkesh Patel (37:49.038) Mmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (38:08.3) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (38:13.966) I don't know that much about this industry. So I don't know what the main use cases for this data are or what is the theory of why it would intrinsically become more valuable with AI. My intuition is that it's not that useful for AI training. For AI training, think it's just genuinely getting the raw. It would be much better to have, here's how you write software better, kind of.

Auren Hoffman (38:28.962) Yep. I don't think so either.

Dwarkesh Patel (38:42.168) building environments made for AIs to practice in kinds of stuff, not like here's a couple hundred million tokens of spreadsheets. So then there's a question of, OK, well, what else is that data useful for AIs? And I'm not sure. Maybe there's an answer. But yeah, what's the theory of why it's supposed to become more valuable with AI?

Auren Hoffman (39:07.244) Well, I don't know that there is a theory, but I think a lot of people are having most of these data companies today. They're, they're way more profitable than they were a couple of years ago because just like creating the data is easier than it was before. And so they've been able to get costs out and they maybe haven't yet passed that those costs onto their customers. so there's this big profitability Delta.

Dwarkesh Patel (39:09.87) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (39:18.903) Interesting.

Dwarkesh Patel (39:30.798) Hmm

Auren Hoffman (39:33.506) But at some point, like they're, all in a very competitive industry. At some point, they'll probably start passing on those costs to the customers. And then they won't be any profit more profitable than they were. let's say a few years ago, that's out there.

Dwarkesh Patel (39:43.214) Mm.

Who are their main customers right now?

Auren Hoffman (39:48.898) I mean, every data company is different. So you just think of like, just think of like any type of data company you've ever thought of, okay, data that sells to real estate or data that sells to hedge funds, data that sells to marketing, data that sells to, you know, academia, data that sells to, you know, there's so many different kinds of data companies that are out there that, that sell. Um, and part of the problem is it's, it's, um, it's hard to, uh, it's hard to use the data.

Dwarkesh Patel (39:58.028) Right.

Auren Hoffman (40:14.006) And so off, sometimes you're selling like software companies who then take that data and like put it in a product to make that, make it sing in some sort of way.

Dwarkesh Patel (40:14.296) Mm-hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (40:21.794) Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Interesting.

Auren Hoffman (40:25.846) The number of users has not gone up very much.

Dwarkesh Patel (40:28.96) Right, yeah, yeah. would, unfortunately, I have no insights on, which is tragic given the title of this podcast, but.

Auren Hoffman (40:37.664) No, what, what, I really wanted to ask you about. So when I think of you, think of like an incredibly curious person. and in some ways that is, it's almost, that's like the it factor in like, that's, that's one of the things we really want more. It would be great if we could have like 10 X more people who are really curious in this world. Is there a way to manufacture that somehow?

Dwarkesh Patel (41:13.634) I think curiosity is often driven by meditating on your own confusion. I think it's very easy to just keep reading stuff or think you're learning and never pause and ask, wait, do I really understand something? I have this experience all the time, I don't know if you have this experience, where I thought I understood something and then I've been reading a book about a topic and I'm a dozen hours in and then somebody asks me the most

basic question, like, how does the concept day work? And I'm like, I have no idea. And I'm like, wait, so then like, what have I been learning exactly? And I guess I've become more more aware that there's these huge holes in my understanding. And I had to become more aware of it because that's how I prepare for my podcast. When I'm interviewing somebody, I'm just noticing, trying to notice, wait, what is the stupid question?

Auren Hoffman (41:53.154) You're right, totally.

Dwarkesh Patel (42:12.482) that or the basic question that I still feel is a big crux that I don't feel fully clarified on. And then once you notice it, you can't stop thinking about it. I just get super excited. I'm just thinking about the upcoming interview. And I cannot wait for them to tell me. If they don't give me a good answer, I'll keep hassling them because I really want to know the answer. And so how do we make more people curious?

putting people in a position where they can notice their own confusion, the blind spots in their understanding. think one way, this is a sort of micro solution. I found it really helpful to have LLMs act as a Socratic tutor, which is to say that like you give them a problem that says, explain concept Y to me, do not move on until you're fully satisfied that I've understood the concept. Ask me test questions, do not move on until I've answered.

understood the relevant sub-concept to your satisfaction before explaining more. And it's crazy how much, you know, this is like such a much more effective and faster way to learn and you like realize how much hidden...

Auren Hoffman (43:21.954) So that, extra sentence of do not move on quiz me, et cetera, that's the, actually is the key sentence. Not the first one in a way. Right.

Dwarkesh Patel (43:25.549) Yes.

Dwarkesh Patel (43:29.442) Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah, what's your answer? How do you stay curious?

Auren Hoffman (43:34.882) I don't know, but I think you're right, but sometimes my learning is not very, you, listen to a whole book and then, um, or you read a whole book or you, whatever it is that you, you, have, you listen to 16 podcasts about why. And then, uh, six months later, you don't, you, you, you, you don't retain anything. So maybe, maybe you did learn during the moment. don't know. Maybe I'm actually not learning during the moment from reading or, but my retention is not high.

Dwarkesh Patel (44:06.146) Yeah, I find it.

Auren Hoffman (44:06.252) Sometimes I, I've read this book that I have, I have a list of books that I love. I have this list of 42 books that I, that I send to people. then recently one of my friends asked me about some of them and I have this book, the, I read this book 10 years ago and I put it on the list because I thought it was like one of the defining books that someone should read. And now I, I really barely even remember what's in that book.

Dwarkesh Patel (44:10.947) Yeah?

Dwarkesh Patel (44:31.106) Right, yeah. This is another one of those boring strategies that I recommend to people, is not some grand this will, this is like, but it is a boring thing which works. It's space repetition. And it's crazy how well it works. It works so well that I regret all the years I've been doing the podcast without using it, because I feel like I would have actually learned something from all these interviews that I did before starting it, which has just sort of,

totally slipped through my mind. And it's crazy how often I'll make space repetition cards for stuff. that...

Auren Hoffman (45:08.642) Sorry, I don't exactly know what you're talking about. So why don't you explain it.

Dwarkesh Patel (45:12.204) yeah, yeah, sorry. Yeah, yeah. It's basically you make flashcards and then there's a software. And what the software does is every so often it'll resurface the card and add quiz you on it. And you make the card and it...

Auren Hoffman (45:26.754) So you just spend like X hours a week just doing this?

Dwarkesh Patel (45:31.8) Yeah, yeah. The harder part is writing the cards because you gotta pause yourself while you're reading something in order to ask yourself, what is the thing I really wanna remember here? The key relationship or fact or conceptual handle, which in and of itself increases your understanding and retention.

Auren Hoffman (45:50.85) So while you're it's kind of like the people who are highlighting, it's like, you know, kind of back in the day, people would like highlight the book or something like that. And I don't even know why they would do it because they would never come back to it. But since you're whatever you're highlighting is almost becomes a card and then you and then you kind of quiz yourself on it later.

Dwarkesh Patel (46:01.667) Yes.

Dwarkesh Patel (46:08.014) Yeah. And the key, one thing the software does is it increases this length of the intervals as you get cards right. So once you make a card, it'll show up tomorrow. Then if you get a ride, it'll show up a week from now. Then if you get a ride a month from now, and then so on. And it's crazy how often I'll be making a card while I'm reading something where I'm like, this is so basic. Like, of course I'm going to remember this, but I got to write something down. So I'll write this down. And then you come back to it a week later and I'm like, I got this wrong.

Or I almost got this wrong.

Auren Hoffman (46:37.986) But what's an example because I would think you'd want to know like, like a fact is not as interesting as like a concept, right? And like, or.

Dwarkesh Patel (46:45.644) You can do both, I would not underrate how important it is to remember facts in order to understand concepts. Like a lot of concepts are just, I'm trying to think of a good example.

Auren Hoffman (46:51.936) Okay.

Dwarkesh Patel (47:03.168) Yeah, for example, an AI, right? Like here's a card you can save. How much has the compute for frontier models increased per year? What's the trend been since 2016? I think it's like 4.5X a year. Okay. So that's just like a raw number you've stored. Like, isn't that just like a useless memorization exercise? Okay. Well, next time you're debating where AI is headed from here, it's very important to know, wait, like what is the key trend? And you can like recall this.

Auren Hoffman (47:30.206) even know that it's 4.5x for the last 10 years every year every year

Dwarkesh Patel (47:33.9) Yeah, something, yeah, yeah, yeah. The size of the frontier, yeah, the amount of compute using the frontier systems, that's right.

Auren Hoffman (47:40.904) I actually didn't realize it was that high. So that's a pretty, that's a, that's an interesting compounder that I didn't understand until right now.

Dwarkesh Patel (47:42.742) Right. Yeah, so.

Yes. And that has all kinds of interesting implications that we can get into, like, that's the kind of thing, that's what I mean is that you, you can now consider those implications if you have that fact cached. Or whenever you encounter the fact again, you'll like, you'll start thinking about, I mean, another thing is it's very hard to learn a concept or learn a field if you're not accumulating these like nuggets of understanding to build, you know, before it felt like,

I'll be trying to understand a difficult topic and every day I'm trying to relearn the exact same like four key words or something or four key concepts and I just wouldn't move on. And now I can like just make the card. It feels like I'm consolidating so I can actually keep stacking my knowledge up over time. I don't know if you do.

Auren Hoffman (48:32.67) I mentioned just like the fact that you make the card is like the the chance that you're going to retain that goes up by 10x or something just by the fact you made the card.

Dwarkesh Patel (48:40.428) Yes. Yeah, yeah. I don't know if you have like screen recordings or whatever. I can just show you what it looks like. But also if this is not what you want to talk about in the podcast, we can just move on. okay.

Auren Hoffman (48:50.57) No, I want to it. Let's see. I loved it. Yeah. I mean, that'd be, that'd be so cool.

Auren Hoffman (48:57.846) And now you make a habit of doing this like.

Dwarkesh Patel (49:01.806) To be honest, I'm quite bad about like, know, some weeks I'll just totally forget and then some weeks I'll go through like the whole stack again and...

Auren Hoffman (49:08.45) And how do you, cause like sometimes like you're in a conversation, like you probably go to these super interesting dinner with a buddy and they tell you all these things. Are you like taking notes and stuff?

Dwarkesh Patel (49:18.678) I don't, but then I don't remember them. Like that's why it's tragic. Cause I've had probably like, I'm very lucky to have friends who have taught me incredible amounts of things. And I'm now thinking about how much I've lost from those conversations because I haven't been consolidating them in a system like this. Cause when I think about like, when I do do is things like this. All right, so just like stuff like this. I normally offset.

I don't know how interesting this will be, I think the answer here is that it makes your exports less competitive. so that the...

Auren Hoffman (49:58.37) So for people who listening, people who are listening to this podcast instead of on video, like walk us through what you're doing here.

Dwarkesh Patel (50:05.452) OK, so question comes up. This one actually, let's just keep these two because I think there are sort of exceptions. Let's start here. OK, so given that there's no verifiable reward for deep research, how can you still do RL on it? And I think the answer is that you have another LLM just give its own subjective evaluation of how good the content was in terms of conciseness or comprehensiveness or these other soft criteria.

Auren Hoffman (50:11.756) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (50:37.685) Now, why is it important to have this card? Or in the long run, why will this matter? Because now I have a better understanding of RL. There's ways to make it work for domains outside of just verifiable rewards. And here's how it might work. This is when I was preparing for Dylan Patel. It would be pretty embarrassing if I keep getting these wrong. what is it, 200 millimeters or something? OK.

Auren Hoffman (50:56.993) Yeah.

Auren Hoffman (51:00.908) Sure, what's common? I don't even know what this means. So what is this? What is this? What is this question? Why is this interesting?

Dwarkesh Patel (51:09.326) This is what wafers in chip production are made of. So first you get this cylinder of silicon, and then it's sliced up. then those wafers are like, that's what you make the dye on top of.

Auren Hoffman (51:16.556) Okay.

Auren Hoffman (51:26.55) Got so one of them is like six inches, one of them is seven inches and one of them is 13 inches or something like that. And why is that important to know?

Dwarkesh Patel (51:32.492) Yeah. Yeah.

That one I honestly don't think is that important to... I wrote it down at the time. Okay, this one is the one that I think is important.

Auren Hoffman (51:38.868) Okay, okay. I'm trying to understand like your, your process here.

Auren Hoffman (51:48.162) So here the question is, why doesn't the 0.5 to 1 % per step error in chemical DNA synthesis do multi mega base projects? So I don't even know what that means. So walk us through like, is that question important?

Dwarkesh Patel (52:04.28) I think I've also forgotten... Let's skip this one. I think the answer is you can stitch them together afterwards. I forgot how. Whatever. I'm gonna mark that as forgotten. We can cut all of this if it ends up being sort of boring, but to the extent that it's interesting, we can keep going through it. Why can adjacent layers in a transformer...

Auren Hoffman (52:12.162) Okay.

Dwarkesh Patel (52:33.858) were thought of as almost parallel because their contributions to the residual stream are additive. So it's a linear contribution, and then linear contributions can be. Anyways, this is probably getting kind of boring. But basically,

Auren Hoffman (52:49.642) Yeah. Well, I guess, I guess the question I have for you is not, not, Like the question I have for you is not necessarily this particular thing, like, like, is the process? you like, decide like, okay, once a week, I'm going to do like a three hour thing or you're on a train and your board. So you just go through it instead of, instead of going on, you know, social media or something or.

Dwarkesh Patel (53:20.43) Um, yeah, I mean, ideally that's the sort of, uh, that's the idea. Um, yeah, when I, I mean, I think the thing is you're supposed to do it daily. I don't, I like sometimes for a build it, build up and then do it once in a while. Um, or did you, yeah, did did you mean it in the sense of like, how do I, how do I like make the cards or?

Auren Hoffman (53:39.362) Yeah. Yeah. Like you have to make it and then you actually have to like remind yourself to do it. Um, and then you have to decide, okay, I'm going to stop doing this now because I'm getting like frustrated or bored with this or whatever. Um, and then of course, like reminding yourself is also impeding new learning. Um, and taking some other time, it's kind of like working out, right? Like working out has some value. You're building some muscle and stuff like that, but

Dwarkesh Patel (53:45.294) Hmm

Auren Hoffman (54:07.842) You just can't do it the whole day.

Dwarkesh Patel (54:09.846) Right, mean, maybe the big picture thing you hear is, look, some of these questions, as I was going through them, I'm like, one part of you is like, why is this information important to remember in the first place? But then you decided to read about it, right? So it must contribute to a world model in some way. If not, why read about it? And if it does contribute to a world model to know how does DNA synthesis work and what are the main constraints to bridging it together.

If that's important to know, why wouldn't you want to remember that? And how are you going to remember that if you don't make some sort of a system like this? And so to the extent that you find something like this monotonous and you're like, okay, why am I, I don't need to remember these facts. Then you should really ask yourself like, why are you reading in the first place? And I think genuinely the answer might be, yeah. And maybe that's it. Like, or maybe I think in many cases, like, yeah, you're like, you're just killing time, but then be honest with yourself.

Auren Hoffman (54:56.002) are you reading in the first place? Like is it just for pleasure? Are you reading just like you'd read for fiction or is it is there?

Dwarkesh Patel (55:08.238) And if it's not just to kill time, then if you're not using a system like this, do you really think you're like remembering the things you're reading? I mean, for me, it's like my job to then, you know, accumulate the things I'm reading, have them cashed in my mind so that if a topic is referenced in an interview, I can, I know what the relevant follow-up could be. Or even when I'm preparing for a future guest, I like have a bunch of ideas baked in my mind.

Ask yourself what the equivalent thing in your career or life is. If there isn't one such thing, maybe, you just like go watch a movie instead. reading's kind of boring, right?

Auren Hoffman (55:43.176) Yeah, there's also I find that there's everyone is different about how they remember and what they remember and so they tend to remember So like for me personally for whatever reason I am just incredibly good at understanding dates and dates relative to one another So if you gave me like 12 history dates, I could I might not tell you Sorry 12 things that happen in history throughout time. I might not I might not be able to tell you like the date it happened, but

I would probably be able to order it on those 12 almost perfectly. so for whatever reason, that's like the thing I can remember really well, but like just other things I'm terrible at. And, and then, and then maybe I just gravitate more to those things that I'm good at remembering. And I kind of go away from the things I'm not. And that might hinder me or might give me some sort of local maxima that I can get because I'm, I'm like, I like the reward of knowing I can remember it or something.

Dwarkesh Patel (56:18.094) Mmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (56:42.734) Hmm. Sorry, the local maxima is the...

Auren Hoffman (56:46.988) Well, if you're good at, I assume that you're good at like remembering a certain type of thing. You like, you like the fact that you're good at it. at least for me, I like the fact I'm good at it. I just like learn more of those types of things. Not going to impress people.

Dwarkesh Patel (56:51.042) Yes.

Dwarkesh Patel (56:58.944) Right, yeah, that's interesting. And this is why people like, this is why people read more history than I think makes sense too. I think people, everybody has like a hundred history books and then like a handful of science books or something because history does have this quality of like, there's like a bunch, it's like really long, there's a sub-history and everything. And yeah, I agree, it is this sort of adverse selection. I don't know if it's adverse, the right term, but.

the selection towards more memorable or more parsable things. Whereas I think like often learning is really hard and like it's not an unwinding experience to go through just like a dense text that really has good explanatory frameworks for something in biology or whatever.

Auren Hoffman (57:48.67) You know, going back to your history thing is really interesting. So I just had, I was just on a long drive and I had two books queued up and one was like the history of chiefs of staff in the white house. And that was the easiest book to listen to. It was like so easy and it was great stories and it was super easy. And then the other one was like this deep analysis of interest rates.

Dwarkesh Patel (58:12.044) Yes.

Auren Hoffman (58:12.246) And this was a terrible book to listen to on a drive. Cause it was just like, it was very, very, very dense and very hard to comprehend. And I probably shouldn't have done it on a drive. I should have actually been reading it and spending time and stopping and, and, you know, and, and so there's also just different modalities that people want information. and like a podcast like this, probably a lot of people are doing something else while they're listening to this podcast. It might be hard to get super deep.

into something because it's like, you don't want to like stop the podcast and like write it down and stuff. Whereas, there might be other types of modalities where you really want to go more deep.

Dwarkesh Patel (58:50.226) Mm-hmm. Yeah, a hundred percent and you even um, you've been on a book like that reading it versus like stopping to anytime some important like Explanation is made make the cards because you realize it like you ask yourself the question. You're like, I actually don't understand So Ken Rogoff I Feel like I'm gonna do like the rabbit hole you have like what is a specific question I had or something, but there's been many cases where I'm like, okay Here's the question that's like obvious that I should ask about this text and wait like I should don't understand

What exactly, how does he explain why this is true? And then you start talking to the LLMs. The LLMs give you a bunch of ideas. then can like, this is another great thing about using AIs is that you can keep asking follow-up questions. So there's this famous effect called Bloom 2 Sigma where this researcher noticed that the effects of having a one-on-one mentor is two standard deviations better than teaching yourself, or sorry, teaching in a group. But you can with.

If you know how to use LLM as well, you can basically create a one-on-one tutor for yourself. And you can just like, you can keep, you don't have to exhaust your list of questions and everything is a rabbit hole. And there's like an immediate way in which you can like keep banging the pinata.

Auren Hoffman (01:00:08.178) I do think this is where a rapper can be helpful because yeah, you, came up with this like smart prompt that I hadn't thought of before there. but like just like better rapper with a nice UI that like game of fires it a little bit and like, some sort of exploding stars when I get four in a row, right. It makes me feel good about it. And, you know, tells me how great I am.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:00:26.392) Hahaha.

Auren Hoffman (01:00:33.302) It gives me some positive encouragement stuff, kind of like Duolingo. Duolingo essentially really, you know, maybe it's just a rapper on these things, but it's it's great. Like people, people actually really like it. Like something like that actually really does have value.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:00:47.982) I've made these kinds of wrappers for myself and I've like stopped using them because the thing about these AI is, is there so general? And so I don't want that. I can like, I wanted to do Socratic tutoring and then sometimes I just want to stop and be like, okay, stop. know, your questions are kind of like, we're moving too slowly. Let's, let's just change this up or more or like, okay, let's stop doing the Socratic thing. And now I just genuinely answer my question in a normal way. Like, like, tell me this or I don't know. It's a good to have the flexibility. So I've still found using the chatbot itself to be.

Auren Hoffman (01:00:55.585) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:01:18.254) the best way to access the full generality of the models.

Auren Hoffman (01:01:23.862) Nope. Is there, is there you, one of the things you're doing is really just working on your craft and becoming a better podcaster. I feel like somehow you just like got out of the gate really good. where it's like most people like over time get much better and they, kind of start out very low basis. And then if they keep working on it, but what are you doing to just like get to the absolute excellent point? Is it just preparation?

Dwarkesh Patel (01:01:50.958) Yeah, well, I I've been doing it for five years. I don't know if I was like, it was good out of the gate. from the inside, it feels quite slow. Like five years is a long time. Now it's an exponential growth process for anybody hearing about it for the first time. They're likely to have heard about it recently, or the average person who's heard about my podcast has heard about it recently. And then sorry, your question was, how do you, how do you keep?

Auren Hoffman (01:02:01.964) Yeah.

Auren Hoffman (01:02:16.748) Like, are you doing something to make yourself just a better podcast or like you're preparing, but is there some other thing you're doing to just become a better podcaster?

Dwarkesh Patel (01:02:22.403) Yes.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:02:28.704) No, mean, I, the main thing I do is I try to learn more things. I, I've been writing more that helps me sort of consolidate my own takes because it's very hard to react to somebody if you don't have your own mental model that you're pushing back using. but fundamentally, I don't think other than that, there's any other skills that I've been rehearsing. Cause if, mean, you know, you think that one of the things that would be involved in being a podcaster and I'd be curious to get your takes on this, but like, you gotta be able to talk.

And I'm, I'm like fine at talking. don't know. I haven't like worked on it. I stutter a lot. I, I'm not that coherent. I'm talk too fast. It was like a common piece of feedback I get, but I it doesn't really matter. Like, um, I just like focus on the content and that makes up for it somehow. Um, how about you? What are you working on to hone the craft?

Auren Hoffman (01:03:16.78) I don't know, but I think in a...

It kind of depends what your listener wants to get out of it. But do you think that most, most of the popular podcasts are way too long and they're, they're, they're much more about entertainment than they are about giving your listener more knowledge and helping your listener be better. so if you just think of like the knowledge per minute on some of these podcasts, I think I've gone down.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:03:31.438) Mmm.

Auren Hoffman (01:03:48.886) And maybe what I could do better is increase that, maybe shorten it somehow. so this is what I'm trying to struggle with is how do you, how do you give your users the, the goal isn't like to make it like social media where you want them to consume as much time with you as possible. In fact, you kind of want the least time for the most bang for your buck.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:03:49.421) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:04:10.348) Right. And especially a lot of these, the thing that takes up so much time is not even entertaining. It's questions you feel like you have to ask. What's your book about? Why did you write it? Where did you grow up? Whatever. Which, like, you know that you don't care about, or to the extent that you, you know, like, who cares where they grew up, right? Their, book is about fucking, sociology, or like, their book is about Russia, like,

Auren Hoffman (01:04:21.568) Yeah.

Auren Hoffman (01:04:37.282) Well, you know, I don't, so this is where I go back and forth on like when it like, so I, I don't, haven't had any of questions of to you about things about where you grew up or all the other types of stuff for your background and stuff like that. But if we were, if you and I were having lunch together, I might actually find that very interesting. and that might help me understand something about you or you may tell me something interesting, interesting anecdote about your sibling or your parents or something that could.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:04:57.134) Mmm.

Auren Hoffman (01:05:06.828) give me a better sense of things. it's very hard to know. Maybe these podcasts like I never do in my podcast, but maybe that is maybe that's a failing of this podcast.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:05:19.372) Yeah, fear, think it's...

Dwarkesh Patel (01:05:24.652) I found it like, there are situations in which I find like a sort of person mysterious and I want to understand what contributed to their mind. like in most cases, I'm just like especially interested, the thing that got me obsessed is just the object level interest in the thing they're studying or have expertise in. And then as they're talking about their own personal life, I'm just like, okay, well, let's get back to, know, whatever.

Um, uh, um, so, but, but more, fundamental. Like, look, if you have, if you figured out a formula where you can actually, I'm probably bad at asking questions about people in a way that reveals interesting things about them. You've got a formula to crack that in a way that's genuinely interesting to you. think it's a ton of sense to ask those questions. The bigger problem I have is with people who, um, ask questions that they aren't interested in, but so

Auren Hoffman (01:05:54.422) Yep, that's a good point.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:06:23.552) If you aren't interested in their personal life or you don't think it's relevant, but still asking it because it feels like something the audience might want to hear about. I've seen some podcasters do things like that, which I think, like, if you don't find it interesting, why do think the audience will find it interesting?

Auren Hoffman (01:06:37.122) Yep. Is there certain people when I like just meet up with them, I have nothing to a podcast. I meet up with them for lunch where I'm pretty much guaranteed to have like a hundred percent interesting conversation from start to finish. And there's certain people where, who you love and where you're really much more in catch up mode with them. Oh, how are things? How are the kids? What's going on? What's happening? What vacations did you go on or something like that? And, but they're

Dwarkesh Patel (01:06:48.568) Hmm.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:06:57.378) That's right. Yeah.

Auren Hoffman (01:07:03.426) you're still some sort of like real value in those things too. And you might not be learning as much as it might not be like intellectually interesting, but there's something still just like great for humanity about those things.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:07:16.866) You think so? I sort of feel like I've become less patient over time. I'm like too young to be a grouch, but every time I have a coffee with somebody, I'm just like, I'm never doing this again.

Auren Hoffman (01:07:21.28) Yeah.

Auren Hoffman (01:07:29.606) You might be right. Yeah. It's funny. I have a friend who is, you know, I would say one of the most interesting people in the world. And I think that he designs his life to only have interesting conversations with people. And he has figured it out somehow that he does not suffer on interesting conversations. And like probably for, for most people, you just have to deal with stuff.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:07:42.893) Hmm.

Auren Hoffman (01:07:54.304) And somehow he has just aligned his life and it just like, then he gets more interesting by default because of that.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:08:01.536) Hmm. Yeah, I am Yeah, 100 % I think a huge flywheel to the podcast has been that I've met smarter people who have taught me a lot of things I in my personal life. I've sort of way over corrected from my job and My new rule in my social life is just nothing can be learned and nothing can be taught It has to be like exclusively stupid banter and riffing and jokes and because

11pm is just a weird time to get somebody's monologue on Chinese EVs. also, this could have just sent me the blog post, like, you're really bad at explaining stuff. But, but yeah.

Auren Hoffman (01:08:34.498) Yeah, yeah.

Auren Hoffman (01:08:44.226) All right. In the interest of like actually practice my preach and keeping this short, have two more questions that we ask all of our guests. One is what is the conspiracy theory that you believe.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:08:57.902) One is that I think the war with, I'm not a historian, I don't have too much at stake in this, I could definitely be wrong. The war with Japan, World War II, America's involvement in World War II, I don't think Pearl Harbor was an inside job or something. This is not my level of conspiracy, but more so the preceding negotiations could have just been handled much smarter on both sides, but since,

The American side is the one that we had control over. We could have avoided the events that led up to Pearl Harbor.

Auren Hoffman (01:09:37.634) Interesting. Yeah. I mean, almost certainly. feel like that we could have, we could, mean, almost certainly we probably could have, right? I don't know that's, is that a, is that a conspiracy theory or

Dwarkesh Patel (01:09:38.99) Yeah, I can go into, I can double click on that, but I don't want to bore you with whatever.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:09:47.552) Yeah, so basically what happened is Japan invaded China, committed horrible atrocities, obviously. And then we embargoed oil on Japan. The Japanese empire could not survive more than like two years if they ran out of oil. And so they're like, okay, well, we're gonna probably lose a war against America.

Auren Hoffman (01:10:07.298) This is like my main, this is my main takeaway from the prize, which is one on that 42 list. Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:10:12.31) Yes. Yeah, yeah. So we're probably going to lose the war if we go to war with America, but we're like definitely going to lose the war if we don't because we're going to run out of oil. And I think like it was not America's main geopolitical objective to take out Japan. The main geopolitical objective was to take out Germany. So and there are multiple like miscommunications where fundamentally problem was the Japanese government.

Auren Hoffman (01:10:22.231) Yeah.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:10:41.322) was had like a civilian dominated part led by Prince Kanui and then the military dominated part by Tojo. there was Americans would get messages from the Japanese side that where we would read them as, they're like, they're double playing us. Sometimes they want to be diplomatic. Sometimes they want to be aggressive. Whereas really, it was just the different parts of the Japanese government trying to get an edge in. And we should have given the more accommodating civilian side.

more room to save face, basically.

Auren Hoffman (01:11:13.772) Yeah. Interesting. Yeah. I have this theory that like, basically like the U S has lost basically every war battle it's ever been in, in the history of the U S but somehow we still win the wars. So it's just cause we just outlast them.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:11:24.276) interesting.

Dwarkesh Patel (01:11:28.504) Huh.

Interesting,